Tagalog: A Modern Guide to the Language of the Philippines

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Introduction: A Language at the Center of a Global Community

Tagalog is one of the major languages of the Philippines and the foundation of the country’s national language, Filipino. It is the everyday language of Metro Manila and large parts of Luzon, a key medium in education, media, and government, and a bridge for millions of overseas Filipinos who live and work around the world. Alongside English, it shapes how people in the Philippines think, joke, negotiate, and build products.

This guide offers a practical overview of Tagalog and Filipino for learners, translators, and product teams. We will look at how Tagalog and Filipino relate, trace the language’s history from precolonial scripts to modern Filipino, unpack the writing and sound system, explain the focus/voice grammar that makes Tagalog special, and explore Taglish—the everyday mix of Tagalog and English. We will end with a learning roadmap, handy phrases, common mistakes to avoid, and notes on AI translation and localization.

Language Overview: Tagalog, Filipino, and Where They Are Spoken

Tagalog belongs to the Austronesian language family, specifically the Central Philippine subgroup. It is related to other Philippine languages and more distantly to Malay, Indonesian, Javanese, Hawaiian, and Māori.

Speaker numbers vary by source, but a reasonable picture looks like this:

- Tagalog as a first language: tens of millions, concentrated in Metro Manila and surrounding regions such as CALABARZON and Central Luzon.

- Tagalog/Filipino as a second language: widely used across the rest of the Philippines as a lingua franca, especially in cities.

- Overseas Filipinos: large communities in the United States, Canada, the Middle East, East and Southeast Asia, and Europe keep the language alive abroad.

Tagalog and Filipino are closely related but not identical.

| Aspect | Tagalog | Filipino |

|---|---|---|

| Status | Regional/ethnic language | National language in the constitution |

| Basis | Traditional Tagalog grammar and vocabulary | Standardized variety based largely on Tagalog |

| Vocabulary | More conservative in some registers | More open to borrowing from other Philippine languages and English/Spanish |

| Use | Home, local media, regional identity | Schools, national media, official communication, national identity |

In practice, people often use the labels “Tagalog” and “Filipino” loosely and interchangeably. For this article, we will say “Tagalog” when focusing on structure and examples, and “Filipino” when talking about the standardized national variety in education and policy.

Regional Variation

While this guide focuses on Manila Tagalog (the basis for standard Filipino), be aware that regional varieties exist. Tagalog spoken in Batangas, Quezon, or other provinces may have distinct vocabulary, intonation patterns, and even some grammatical preferences. Manila/Metro Manila Tagalog is the most widely understood variety and the foundation for media and education.

From Precolonial Scripts to Modern Filipino: A Brief History

The story of Tagalog is tied to migration, trade, religion, and nation-building.

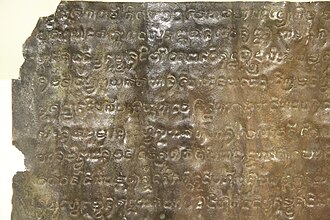

- Precolonial period: Austronesian-speaking peoples settled the Philippine archipelago thousands of years ago. Over time, Central Philippine languages including Tagalog evolved. Before European contact, Tagalog was already used in oral literature and local governance. A syllabic script known as Baybayin (and related scripts) was used to write Tagalog and other languages on materials like bamboo and palm leaves.

-

Spanish colonial era (16th–19th centuries): With Spanish colonization, Catholicism, European administration, and global trade arrived. Spanish became the language of colonial government and high culture, but local languages including Tagalog remained dominant in everyday life. Many Spanish words entered Tagalog, especially for religion, administration, household items, and numbers. Over time, Baybayin receded and the Latin alphabet became the main writing system for Tagalog.

-

American period and the rise of English (late 19th–early 20th centuries): After the Spanish–American War, the United States established colonial rule. English entered schools, law, and administration, introducing a powerful second language that is still official today. Tagalog continued to be used at home and in local print and radio, but English deeply influenced vocabulary and styles of speech.

-

National language policy and Filipino (20th century): In the 1930s, a national language based on Tagalog was chosen as a unifying symbol for the new nation. Over decades, this standard evolved under names like “Pilipino” and later “Filipino”, and was written into the 1987 Constitution as the national language. Filipino is officially defined to evolve by incorporating elements from other Philippine languages and sources.

-

Contemporary era: Today, Filipino and English are both official languages of the Philippines. Filipino, based largely on Tagalog, is the main language of national media and a required subject in schools. English dominates in higher education, business, and law. Everyday speech in cities often blends Tagalog and English in a hybrid known as Taglish, which has become a natural register rather than an exception.

Writing and Pronunciation: Latin Script, Stress, and Glottal Stops

Modern Tagalog uses a Latin-based alphabet, and its spelling is relatively close to pronunciation. This makes the language more approachable than many learners expect.

Script and alphabet

- Alphabet: Contemporary Tagalog/Filipino orthography uses an expanded Latin alphabet (traditionally 20 letters, now often 28 with additional consonants such as

c,f,j,ñ,q,v,x, andzfor names and loans). - Digraphs: The sequence

ngrepresents a single velar nasal sound as in English “sing”; it can appear at the start or middle of words (ngayon,sanggol). - Historical script: Before the Latin alphabet, Tagalog was written using Baybayin, a precolonial abugida. Today, Baybayin is mostly used symbolically—in logos, tattoos, art, and cultural education—while the Latin script is standard for everyday communication.

Sounds and stress

Tagalog has a relatively simple vowel set and a consonant inventory that is familiar to speakers of many other languages.

-

Vowels: Five primary vowels—

a e i o u—similar to Spanish in clarity. They are usually pronounced consistently, without the multiple values seen in English.aas in “father”eas in “bed”ias in “machine”oas in “oh”uas in “food”

-

Consonants: Many consonants align with their English counterparts. Some borrowed sounds (like

f,v) appear mainly in loanwords and modern orthography.ngis pronounced as in “sing” and can start words:ngayon(now)ris typically a single tap/flap, similar to Spanishdandrare sometimes interchanged in casual Manila speech

-

Stress: Word stress is crucial in Tagalog. It can fall on different syllables and, together with a glottal stop (a brief “catch” in the throat, like the middle sound in “uh-oh”), can distinguish words that are spelled the same.

In careful linguistic notation, accents and symbols show where stress and glottal stops occur, for example:

baba(low, chin)babà(downwards)babâ(to go down, depending on analysis)

In everyday writing, these stress marks and glottal stop indicators are usually not written, which means learners must acquire correct stress patterns by listening and practice.

Orthography and pronunciation

- The correspondence between spelling and sound is fairly regular compared to English.

- Loanwords from Spanish and English are adapted to Tagalog phonology and spelling to varying degrees (

mesafrom Spanish “mesa,”kompyuterorcomputerfrom English). - For learners, the main challenges are stress, glottal stops, and learning to hear reduced distinctions in casual speech, rather than complex consonant clusters or tones.

Pro tip for learners: Use online dictionaries with audio (like Tagalog.com or Forvo) to hear stress patterns. This is far more effective than trying to memorize written accent marks.

Grammar Snapshot: Focus, Voice, and Affixes

Tagalog grammar is often described as challenging because it encodes information differently from European languages. The key ideas are focus/voice, particle marking, and rich verb morphology.

The “ang / ng / sa” system

Instead of relying mainly on fixed word order and case endings, Tagalog uses particles to mark different roles:

ang-group: marks the grammatical topic or focused noun (often translated as “the” for the main subject).ng-group: marks non-topic actors or objects (patients, agents, etc. that are not in focus).sa-group: typically marks locations, directions, or recipients.

Example (simplified):

Kumain ang bata ng mangga sa bahay.→ “The child ate mango at home.”

Here:

ang bata— the child (topic/focus)ng mangga— mango (non-topic object)sa bahay— at home (location)

If we change the verb form and the marking, we can bring different participants into focus, even while the overall situation stays similar. This is the essence of the focus/voice system.

Verb focus and affixes

Tagalog verbs are built from roots plus affixes that indicate voice (focus), aspect, and other nuances. Some of the most common affixes include:

- Actor-focused:

-um-,mag-,ma- - Object/patient-focused:

-in-,-hin - Location/benefactive-focused:

-an,i-,ipag-, etc.

These affixes interact with aspect (completed, ongoing, contemplated) through patterns of reduplication and vowel changes.

A simplified table (with a common root bili “to buy”) illustrates the idea:

| Form | Rough meaning | Focus |

|---|---|---|

Bumili ang bata ng mangga. | The child bought mango. | Actor focus (child) |

Binili ng bata ang mangga. | The mango was bought by the child. | Object/patient focus (mango) |

Ibinili ng bata ang kaibigan niya ng mangga. | The friend was bought mango by the child. | Benefactive focus (friend) |

Binilhan ng bata ang kaibigan niya ng mangga. | The friend had mango bought for them by the child (location/benefactive nuance). | Locative/benefactive focus |

In all cases, the root bili is present, but affixes and particles reshape which participant is in focus and how the event is viewed.

Understanding the shift: The key insight is that changing focus doesn’t fundamentally change what happened, but rather what you’re emphasizing. In English we might say “The child bought mango” or “The mango was bought by the child”—the second is passive. In Tagalog, both sentences can be active in meaning, but they focus on different participants.

Aspect more than tense

Tagalog distinguishes aspect more strongly than tense:

- Completed (perfective): action seen as whole (

kumain– ate/has eaten) - Incomplete or ongoing (imperfective): action in progress or habitual (

kumakain– is eating / eats) - Contemplated: action not yet started (

kakain– will eat / is about to eat)

These patterns combine with focus affixes to create a rich verb system. Instead of directly encoding “past vs present vs future,” Tagalog often encodes whether an event is completed, ongoing, or intended.

Example with the root kain (eat) in actor focus:

| Aspect | Form | Meaning |

|---|---|---|

| Completed | Kumain ako ng tinapay. | I ate bread. |

| Ongoing/Incomplete | Kumakain ako ng tinapay. | I am eating bread. / I eat bread. |

| Contemplated | Kakain ako ng tinapay. | I will eat bread. |

Notice the reduplication pattern: the first syllable of the root is repeated in the ongoing form (ku-**ka**-kain), and a different pattern appears in contemplated (**ka**-kain).

Pronouns and inclusivity

Tagalog pronouns encode number and, importantly, inclusive vs exclusive “we”:

ako— Iikaw/ka— you (singular)kami— we (exclusive, not including the listener)tayo— we (inclusive, including the listener)kayo— you (plural, also used as a polite singular)sila— they

Inclusive/exclusive “we” is crucial for politeness and clarity. Saying tayo invites the listener into the group; kami does not.

Example:

Pupunta kami sa palengke.— “We (not you) are going to the market.”Pupunta tayo sa palengke.— “We (including you) are going to the market.”

Reduplication and word formation

Reduplication (repeating part of the root) adds nuance:

lakad(walk) →lalakad(will walk),naglalakad(is walking)unti(few) →paunti-unti(little by little)bili(buy) →bibili(will buy),bumibili(is buying)

This makes Tagalog both systematic and expressive, but also means that naïve word-for-word translation can be misleading if it ignores affixes and reduplication.

Putting it all together: A detailed example

Let’s analyze a complete sentence:

Binilhan ng nanay ang anak niya ng bag sa mall.

Breaking it down:

Binilhan— past tense, locative/benefactive focus of rootbili(buy)ng nanay— by the mother (actor, non-focus, so marked withng)ang anak niya— her child (beneficiary, in focus, so marked withang)ng bag— a bag (object, non-focus)sa mall— at the mall (location)

Translation: “The child was bought a bag by the mother at the mall.” Or more naturally: “The mother bought her child a bag at the mall,” but with emphasis on the child as recipient.

If we changed to actor focus, it would be:

Bumili ang nanay ng bag para sa anak niya sa mall.

- Now

ang nanay(the mother) is in focus - Translation: “The mother bought a bag for her child at the mall.”

Both describe the same event, but the grammatical packaging differs.

Common Learner Mistakes and How to Avoid Them

Understanding common pitfalls can accelerate your progress:

1. Wrong particle with the focused noun

❌ Kumain ng bata ang mangga. (The mango ate the child?!)

✅ Kumain ang bata ng mangga. (The child ate the mango.)

Fix: Remember that ang marks the focused participant. In actor-focus verbs (kumain), the actor gets ang.

2. Ignoring stress and glottal stops

basa(wet) vsbasà(read)puno(tree) vspunò(full)

Fix: Listen actively to native speakers. Use audio dictionaries. Stress mistakes can cause real confusion.

3. Direct translation from English word order

❌ Ako gusto kumain. (literal: “I like eat”)

✅ Gusto kong kumain. (I want to eat.)

Fix: Learn Tagalog patterns, not English + Tagalog words. The verb-linking structure is different.

4. Mixing up kami and tayo

❌ Using kami when inviting someone: Kain kami!

✅ Kain tayo! (Let’s eat! — including you)

Fix: Think about whether the listener is included in “we.”

5. Overusing or underusing po

Too much: Kumain po ako po ng tinapay po. (awkward)

Too little: Kumusta ka? to an elder (impolite)

Fix: Add po once per sentence or question when speaking to elders/strangers. For yes/no, use opo and hindi po.

6. Forgetting that aspect ≠ tense

❌ Thinking kumain can only mean “ate” (past tense)

✅ Kumain means completed action, which could be “ate,” “has eaten,” or even recent completion.

Fix: Focus on whether the action is done, ongoing, or planned—not on English past/present/future.

Everyday Tagalog and Taglish in Real Life

In modern Philippine cities, you rarely hear “pure” Tagalog or “pure” English in casual speech. Taglish—the fluid mixing of Tagalog and English—is normal in conversation, social media, and even advertising.

Examples (simplified):

Mag-meeting tayo later sa office.→ “Let’s have a meeting later at the office.”Nag-drive siya papunta sa mall.→ “He/She drove to the mall.”

Here, Tagalog affixes (mag-, nag-), particles (tayo, sa), and syntax frame English nouns and verbs (meeting, later, office, drive, mall).

Key points:

- Register and audience:

- Formal speeches, news broadcasts, and legal texts tend to use more standardized Filipino with fewer English insertions.

- Advertising, social media, and everyday chat embrace Taglish to sound natural and modern.

- Politeness:

- Particles like

poand forms likeopoare used to express respect, especially when addressing elders, clients, or authority figures. - Code choice (more English vs more Tagalog) can signal formality, education, or intimacy.

- Particles like

For translators and localization teams, Taglish is not just “noise”—it is a stable pattern of bilingual speech. Deciding when to use mostly Filipino, balanced Taglish, or mostly English is part of good localization for the Philippine market.

Learning Roadmap: From Zero to Conversation

Tagalog rewards a strategic approach. Here is a roadmap for learners.

1. Master sounds, stress, and basic spelling

- Start with the five vowels and common consonants/digraphs (

ng,ny). - Listen to native audio early to internalize stress patterns and glottal stops.

- Resources: Forvo.com for pronunciation, YouTube channels like “Learn Tagalog with Fides”

2. Learn high-frequency particles and pronouns

- Focus on

ang,ng,sa,si, and personal pronouns (ako,ikaw,kami,tayo, etc.). - Build mini-sentences like

Ako si ...(“I am …”),Nasa bahay ako.(“I am at home.”).

3. Build a core verb toolkit

- Choose common roots:

kain(eat),inom(drink),punta(go),bili(buy),gawa(do/make),kuha(take/get). - Learn their actor-focused forms (

kumain,uminom,pumunta,bumili) and basic aspect patterns (completed, ongoing, contemplated). - Practice: Create simple daily sentences:

Kumain ako ng almusal.(I ate breakfast.)

4. Understand focus/voice step by step

- Start with actor-focused sentences, then gradually explore patient-focused and benefactive-focused forms.

- Compare pairs like

Bumili ako ng kape.vsBinili ko ang kape.and pay attention to which noun takesang. - Don’t rush this—it takes months to internalize.

5. Embrace Taglish without losing structure

- Expect English words inside Tagalog sentences.

- Use this to your advantage: you can express more ideas while still practicing Tagalog grammar and particles.

- Example:

Nag-study ako para sa exam.(perfectly natural)

6. Balance input and output

- Input: Watch Filipino dramas (on Netflix, iWantTFC, Viu), vlogs (try Cong TV, Mimiyuuuh), and news (GMA News, ABS-CBN); listen to OPM (Original Pilipino Music) with lyrics—artists like Ben&Ben, Moira Dela Torre, SB19.

- Output: Write short diary entries, send simple messages to language partners (iTalki, HelloTalk), and practice speaking aloud daily, even for 5–10 minutes.

7. Find conversation partners

- iTalki and Preply for paid tutors

- HelloTalk and Tandem for free language exchange

- Filipino community groups on Facebook and Discord

8. Use AI and other tools wisely

- Check your sentences with a good Tagalog/Filipino translator, but always review how focus, politeness, and Taglish are handled.

- Treat machine output as a reference, not a perfect model.

- Tools: OpenL Tagalog Translator, Google Translate (improving), ChatGPT for explanations

With consistent daily practice (20-30 minutes), a motivated learner can reach basic conversational ability in 6–12 months and develop comfortable comprehension for everyday content within 1–2 years, especially with access to native speakers or immersive media.

Handy Phrases (With Notes)

Here are some useful phrases to get you started, many of which you will hear every day.

Greetings and small talk

Kumusta?— How are you?Mabuti. Ikaw?— I’m fine. And you?Kumusta po kayo?— How are you? (polite, to elders)Magandang umaga.— Good morning.Magandang gabi.— Good evening.Paalam.— Goodbye.

Politeness and thanks

Salamat.— Thank you.Maraming salamat.— Thank you very much.Salamat po.— Thank you (polite).Walang anuman.— You’re welcome.Pasensya na.— Sorry / Excuse me (for inconvenience).Paumanhin.— A more formal “sorry.”

Yes/No and respect

Oo.— Yes.Hindi.— No.Opo.— Yes (polite, to elders or in formal contexts).Hindi po.— No (polite).

Introductions and origins

Ako si ...— I am …Ano ang pangalan mo?— What is your name?Ano po ang pangalan ninyo?— What is your name? (polite)Taga-saan ka?— Where are you from?Taga-[bansa/lugar] ako.— I am from [country/place].

Daily needs

Magkano ito?— How much is this?Magkano po?— How much? (polite)Saan ang banyo?— Where is the bathroom?Nasaan ang ...?— Where is …?Pakisara ng pinto.— Please close the door.Puwede bang magtanong?— May I ask a question?Hindi ko maintindihan.— I don’t understand.Puwede bang mabagal?— Can you speak slower?

Useful connectors

Pero— ButKasi— BecauseKaya— So / ThereforeAt— AndO— Or

Note that adding po (e.g., Kumusta po?, Magkano po ito?) makes the sentence more polite when speaking to elders or strangers.

AI Translation, Taglish, and Localization

For AI translation and localization, Tagalog presents both challenges and opportunities.

Challenges

-

Rich morphology and focus/voice

- Affixes (

mag-,-um-,-in-,-an, etc.) carry grammatical information that does not map neatly to English tenses or passive/active voice. - Incorrect handling of focus can produce sentences that are grammatical but subtly wrong about who did what to whom.

- Affixes (

-

Taglish and code-switching

- Real-world data is full of Tagalog–English mixtures at the word, phrase, and clause level.

- Many generic machine translation systems are trained on cleaner, single-language text and may produce awkward output when faced with Taglish.

-

Politeness and register

- Nuances like

po/opo, choice of pronouns (kayovsikaw), and register shifts can be hard for models to control, especially across domains (customer support vs advertising vs legal).

- Nuances like

-

Context dependence

- Tagalog often drops pronouns when context is clear. AI systems may struggle to infer the right subject or restore it in translation.

Opportunities

-

High-impact improvements

- Better Tagalog/Filipino and Taglish handling can dramatically improve user experience in customer support chats, e-commerce, fintech, and healthcare contexts where many Filipino professionals and customers operate.

-

Domain adaptation

- With enough in-domain data (for example, support tickets or product descriptions), AI models can learn more natural combinations of Tagalog, Filipino, and English and can adapt tone to match brand voice.

-

Cultural resonance

- Products that handle Taglish naturally feel more authentic to Filipino users. Over-formalized Filipino or awkward English can make interfaces feel foreign.

Best practices for localization teams

- Choose the right register: Customer support benefits from warm Taglish with

po; legal/medical may need more formal Filipino. - Test with native speakers: Have Filipino team members or testers review translations for naturalness and politeness.

- Don’t over-translate: Some English terms (e.g., “login,” “download,” “app”) are commonly used in Taglish and don’t need Filipino equivalents.

- Consider regional variation: If targeting specific regions, test whether Manila Tagalog is well understood.

AI-powered tools like the OpenL Tagalog Translator aim to handle both standard Filipino and the mixed-language reality of Taglish more accurately than generic systems. For learners, such tools can double as a language partner: you can experiment with different focus constructions or politeness levels and see how they affect the translation; for teams, they help keep content natural and consistent across interfaces and support channels.

Conclusion

Tagalog, and its standardized national form Filipino, sit at the heart of the Philippines’ linguistic landscape and its global diaspora. The language combines a straightforward alphabet and transparent sound system with a sophisticated focus/voice grammar and a deeply bilingual everyday environment shaped by English.

For learners, this mix can be challenging, but it offers a rich and rewarding path into Philippine culture, media, and relationships. The focus/voice system, once internalized, reveals an elegant logic for organizing information. The Taglish environment means you can communicate effectively even while still building your Tagalog foundations.

For translators and product teams, understanding Tagalog, Filipino, and Taglish is essential for building experiences that feel truly native to users in and from the Philippines. The key is not to aim for textbook purity, but rather to match the register, politeness level, and code-mixing patterns that your audience actually uses.

Whether your goal is to chat with friends and colleagues, serve Filipino customers, or localize products for a fast-growing market, taking the time to understand how Tagalog works—from ang/ng/sa particles to Taglish code-switching to the inclusive/exclusive “we” distinction—will pay off in clarity, respect, and connection.

Remember: language learning is a marathon, not a sprint. Be patient with yourself, embrace mistakes as learning opportunities, and engage with the vibrant Filipino community online and offline. Kaya mo ‘yan! (You can do it!)

Sources and Further Reading (selected):

- Tagalog language and Filipino language entries (major encyclopedias and linguistic surveys)

- Historical overviews of Baybayin and Philippine scripts

- Academic work on Philippine-type focus/voice systems and Austronesian alignment

- Descriptive grammars and learners’ resources on Tagalog/Filipino pronouns, aspect, and affixation

- Media and corpus studies on Taglish and bilingual speech in Metro Manila

- Schachter & Otanes (1972): Tagalog Reference Grammar — classic comprehensive reference

- Himmelmann (2005, 2008): Articles on Philippine-type voice systems

- OpenL Tagalog Translator

- Online Resources:

- Tagalog.com — dictionary with audio

- Forvo.com — pronunciation database

- r/Tagalog on Reddit — active learner community