Polish: A Clear Guide to a Major Slavic Language

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Introduction

Polish (polski) is a major West-Slavic language spoken primarily in Poland and by millions in the diaspora worldwide. It belongs to the Lechitic subgroup of Slavic languages and is written with a Latin-based alphabet enriched with several unique diacritical characters. With approximately 40 million native speakers and an estimated 60 million total speakers including second-language users, Polish plays a significant role in Central and Eastern Europe and serves as one of the 24 official languages of the European Union.

For learners and linguists alike, Polish offers a fascinating window into Slavic linguistic systems and Central European history. Its complex morphology and rich phonological inventory make it a compelling subject for comparative linguistic study.

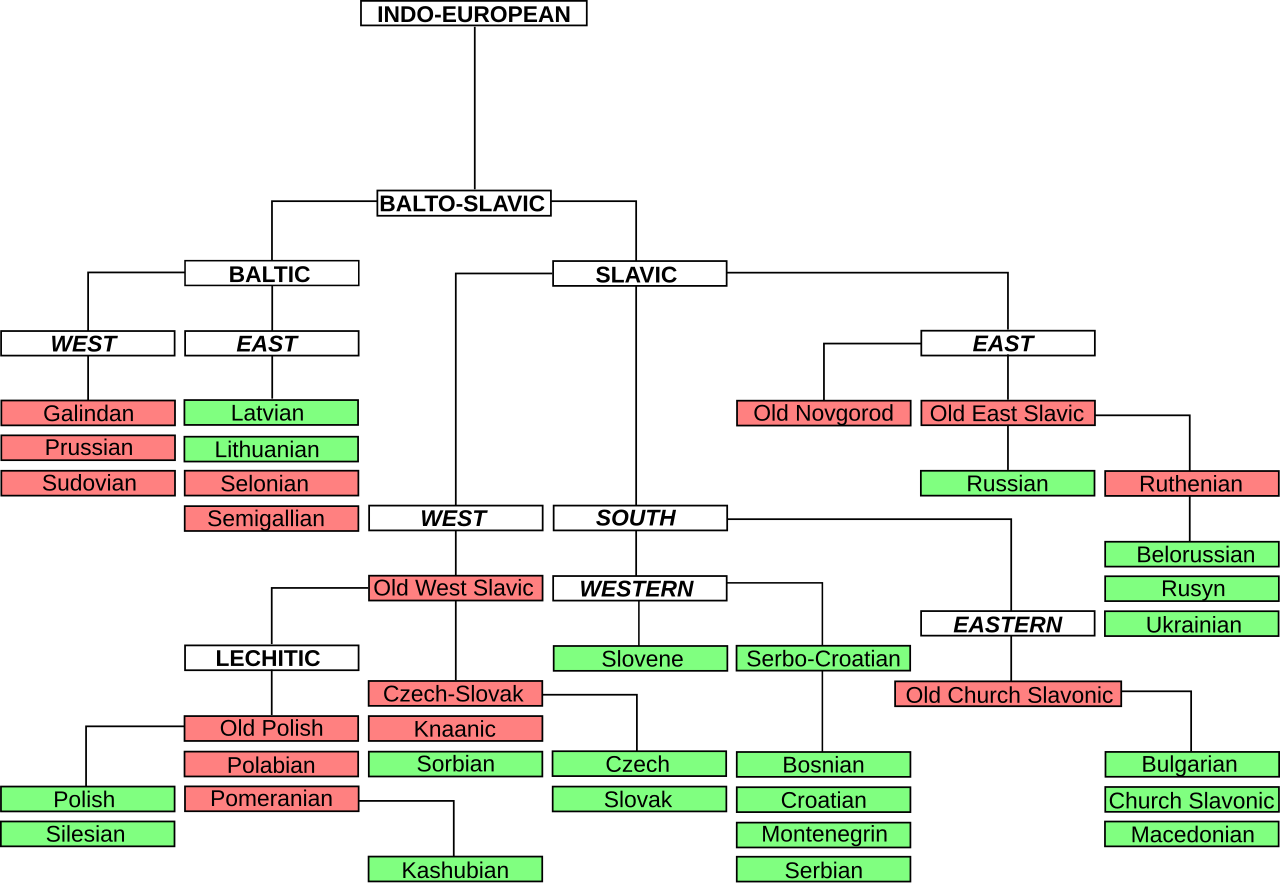

Linguistic Classification

Within the Indo-European language family, Polish occupies a specific and well-defined position. It belongs to the Balto-Slavic branch and falls within the Slavic group, specifically the West Slavic branch and the Lechitic subgroup. Its closest linguistic relatives are Czech, Slovak, and the now-extinct Polabian language—languages with which it shares not only structural similarities but also a common historical trajectory.

Key structural similarities with related languages include:

- Complex inflectional morphology with extensive case systems

- Rich aspectual verb systems distinguishing perfective and imperfective actions

- Palatalized consonant phonemes

- Shared etymological vocabulary from Proto-Slavic

This classification accounts for both the synchronic (contemporary) structure and the diachronic (historical) development of the language.

Historical Evolution

Proto-Slavic Roots

Polish descends from Proto-Slavic, the reconstructed common ancestor of all Slavic languages. The early Slavs inhabited Eastern Europe around the 5th–6th centuries AD, gradually expanding their territorial and linguistic sphere. Over centuries, their relatively unified speech fragmented into the three major branches we recognize today: West Slavic, East Slavic, and South Slavic. This diversification reflects both geographical separation and sustained contact with neighboring language groups.

Old and Middle Polish

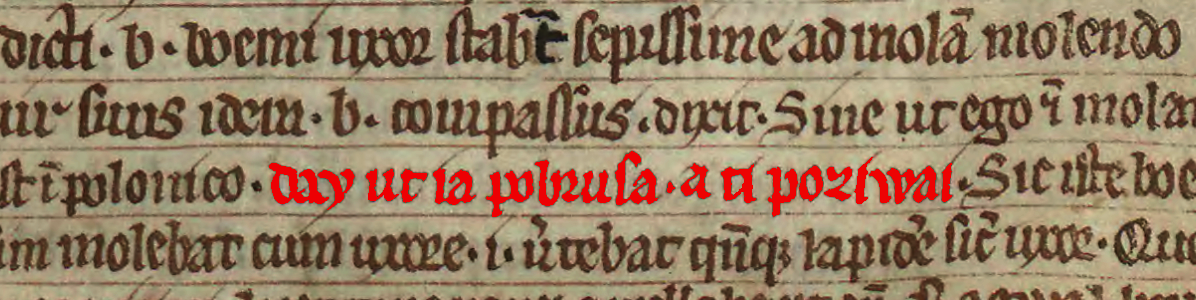

Polish emerged as a distinct and recognizable language in the 10th century, coinciding with the formation of the Polish state under the Piast dynasty. The period of Old Polish (10th–16th centuries) was characterized by regional dialects with limited standardization, despite the growing influence of the Church and literacy.

Key milestone: The earliest known Polish sentence—Day, ut ia pobrusa, a ti poziwai (“Come, let me grind, and you take a rest”)—appears in the Book of Henryków, dated to approximately 1280. This precious documentary evidence reveals the language’s phonological and morphological features at a crucial stage of its development.

The Middle Polish period (16th–18th centuries) coincided with the Renaissance and the “Golden Age” of Polish literature and culture. During this era, orthography and grammar underwent systematic codification, and Polish served as a lingua franca throughout the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth—a multilingual political entity spanning much of Eastern Europe.

Notable literary achievements of this period include:

- Jan Kochanowski’s poetry, establishing Polish as a language of high literature

- Religious texts and biblical translations that standardized religious terminology

- Grammatical treatises that formalized rules for educated speakers

Standardization and Modern Polish

Standardization accelerated dramatically in the 16th century, culminating in a widely adopted written form based primarily on the Greater Poland dialect, which possessed significant prestige and geographic centrality. This standardization process was gradual and contested, reflecting broader questions about which regional variety should represent the “standard.”

After World War II, Standard Polish (język ogólnopolski) became the dominant spoken variety across the country, promoted through education, media, and cultural institutions. This process led to the gradual decline of many local dialects, though regional features persist in everyday speech, particularly in rural areas and among older generations.

Contemporary standardization efforts continue through institutions like the Polish Language Council (Rada Języka Polskiego), which issues recommendations on usage and registers new vocabulary, particularly loanwords and technical terminology.

Phonology and Orthography

Alphabet and Diacritics

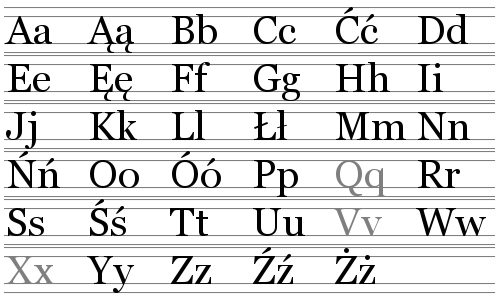

Polish employs a 32-letter alphabet derived from the Latin script, expanded and modified for Slavic sounds. Nine letters feature diacritics that fundamentally alter pronunciation and carry phonemic significance:

| Letter | Function | Example |

|---|---|---|

| ą, ę | Nasal vowels | mąka (flour), gęsty (dense) |

| ć, ń, ś, ź | Palatal (soft) consonants | ciało (body), siła (strength) |

| ł | Dark “L” sound (velarized) | łąka (meadow) |

| ó | Historical vowel shift | stół (table) — pronounced like ‘u’ |

The letters Q, V, and X do not appear in native Polish words, appearing only in foreign loanwords. These diacritics preserve phonemic distinctions that are crucial for meaning: for instance, s (hard) versus ś (soft) represent different consonants entirely.

Vowel and Consonant Inventory

Vowels: Polish has six oral vowels (a, e, i, o, u, y) and two nasal vowels (ą, ę). The language has no phonologically long vowels, and vowel reduction is minimal—unstressed vowels retain their quality, contributing to the language’s clear pronunciation.

Consonants: The consonant system features a large inventory of palatal (soft) consonants, produced with the middle of the tongue raised toward the palate. These include both single letters (ć, ń, ś, ź) and digraphs/trigraphs: cz (affricate), sz (fricative), rz (fricative), dz, dź, and dżw. English has no precise equivalents for many of these sounds, making them challenging for native English speakers.

Common consonant clusters: Polish permits complex consonant clusters both at the beginning and end of syllables—skręt (“turn”), trzask (“crash”), pstrąg (“trout”)—which contribute to its distinctive sound but often challenge learners.

Stress and Prosody

Stress in Polish is fixed predominantly on the penultimate (second-to-last) syllable of each word, a feature that distinguishes it from many other European languages. This regularity makes Polish relatively predictable regarding stress placement.

Exceptions include:

- Certain verb forms, particularly imperatives and past-tense forms

- Many loanwords from French, German, and English, which retain their original stress patterns (kOMputER, inTERnet)

- Prefixed verbs, where stress sometimes shifts based on aspect or mood

Polish has a syllable-timed rhythm, in which each syllable receives roughly equal temporal weight, rather than the stress-timed rhythm of English. This contributes to Polish speech’s characteristic cadence and is often noticeable to English speakers.

Morphology and Grammar

Nominal Morphology: Cases, Gender, and Number

Polish nouns, pronouns, and adjectives inflect for seven grammatical cases, each marking a different syntactic and semantic relationship:

- Nominative — subject of the sentence

- Genitive — possession, negation, partitive

- Dative — indirect object, beneficiary

- Accusative — direct object, direction toward

- Instrumental — agent, means, accompaniment

- Locative — location, temporal reference

- Vocative — direct address

Each case has distinct singular and plural forms. Additionally, nouns are assigned to one of three grammatical genders: masculine, feminine, or neuter. These genders are not always semantically predictable and must be learned with each noun.

Example: The noun kot (“cat,” masculine)

| Case | Singular | Plural |

|---|---|---|

| Nominative | kot | koty |

| Genitive | kota | kotów |

| Dative | kotu | kotom |

| Accusative | kota | koty |

| Instrumental | kotem | kotami |

| Locative | kocie | kotach |

| Vocative | kocie | koty |

Adjective agreement: Adjectives must agree with their nouns in case, number, and gender simultaneously. For instance, “the beautiful cat” requires the adjective piękny to match kot’s masculine singular nominative form: piękny kot. Change the case, and the adjective changes: pięknego kota (accusative), pięknym kotem (instrumental).

Special masculine distinction: Polish distinguishes between personal masculine plural (referring to groups including at least one man or boy) and non-personal masculine plural (inanimate objects or groups of women/girls). This distinction affects not only adjectives but also verb agreement: oni są (“they are”—personal masculine) versus one są (non-masculine plural).

Verbal System: Aspect and Tense

Aspect is the most distinctive feature of Polish verbs, far more central than in English. Each Polish verb exists in two aspects: imperfective and perfective, signaling fundamentally different perspectives on an action.

Imperfective verbs describe actions as ongoing, repeated, or incomplete. They conjugate for three tenses:

- Present: czytam (I read/am reading)

- Past: czytałem (I was reading/read repeatedly)

- Future (compound): będę czytać (I will be reading)

Perfective verbs describe actions as completed or bounded in time. They conjugate for:

- Past: przeczytałem (I read/finished reading)

- Future (simple): przeczytam (I will read and finish)

Note the prefix prze- in the perfective form, exemplifying how prefixation often marks perfective aspect.

Mood and agreement: Polish verbs also distinguish three moods:

- Indicative — statements and questions

- Conditional — hypothetical situations (bym + past-tense form)

- Imperative — commands

In the past tense, verbs conjugate for gender and number: czytałem (I read—masculine), czytałam (I read—feminine), czytaliśmy (we read—personal masculine plural), czytały (they read—non-personal plural).

Syntax and Word Order

Although the unmarked (neutral) word order is SVO (Subject–Verb–Object)—Jan widzi psa (“Jan sees the dog”)—Polish syntax is highly flexible due to its rich case system. The same sentence can be rearranged without creating ambiguity:

- Psa widzi Jan — the dog sees Jan (different meaning but clear from cases)

- Widzi Jan psa — Jan sees the dog (slightly unusual but comprehensible)

- Widzi psa Jan — sees the dog Jan (very marked but grammatical)

This flexibility serves information structure: speakers use word order to highlight topic (what is being discussed) and focus (new or emphasized information). In formal speech and writing, SVO predominates; in informal speech, more variation appears.

Negation special feature: Negation often triggers the genitive case for direct objects rather than the expected accusative:

- Positive: Widzę psa (I see the dog—accusative)

- Negative: Nie widzę psa (I don’t see the dog—genitive)

This negation-triggered case shift is a hallmark of Polish grammar.

Lexicon and Borrowings

Slavic Core Vocabulary

Polish retains a substantial body of inherited Slavic lexicon, providing a foundation of mutual intelligibility with other West-Slavic languages. These basic vocabulary items descend from Proto-Slavic and reflect the language’s ancient roots:

- dom (“house”) — cognate with Czech dům, Slovak dom

- matka (“mother”) — cognate with Czech matka, Russian мать (mat’)

- czas (“time”) — cognate with Czech čas, Slovak čas

- woda (“water”) — cognate with Czech voda, Russian вода (voda)

These shared cognates facilitate some mutual comprehension among Slavic speakers and reveal the common ancestry of modern Slavic languages.

Loanword Strata and Integration

Borrowings constitute approximately 26.2% of Polish vocabulary, reflecting centuries of contact with neighboring and distant cultures.

Historical loanword sources:

| Source | Period | Examples | Contribution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Latin | Medieval–Renaissance | uniwersytet (university), kościół (church) | Legal, religious, scholarly terms |

| German | Centuries of contact | szlafrok (bathrobe), piec (stove) | Everyday and technical words |

| French | 17th–19th centuries | randka (date, from rendez-vous), bilet (ticket) | Cultural and social vocabulary |

| English | 20th–21st centuries | komputer (computer), internet, weekend | Technology and contemporary lifestyle |

| Italian | Trade period | fortuna (fortune), opera | Cultural and commercial terms |

Assimilation process: Polish does not merely transplant foreign words unchanged. Instead, it systematically adapts them to Polish phonological and morphological patterns:

- English coffee → Polish kawa (fully assimilated)

- English computer → Polish komputer (phonologically adapted)

- French rendez-vous → Polish randka (semantic shift and morphological adaptation)

Loanwords receive Polish inflectional endings, allowing them to function fully within the grammar: komputer becomes komputera (genitive), komputerem (instrumental), etc.

Word Formation Strategies

Polish exhibits highly productive derivational morphology, enabling speakers to generate new words systematically:

Diminutives: dom (house) → domek (small house), domeczek (tiny house); kot (cat) → koteczek (little cat)

Augmentatives: dom → domisko (big house), domina (large house, slightly pejorative)

Abstract nouns: czytać (to read) → czytanie (reading), pisać (to write) → pisanie (writing), pisarz (writer)

Verb derivation: Prefixes transform imperfective verbs into perfectives:

- pisać (to write—imperfective) → napisać (to write and finish—perfective)

- jechać (to go/drive—imperfective) → pojechać (to depart—perfective)

Suffixation for agent nouns: nauczać (to teach) → nauczyciel (teacher, masculine), nauczycielka (teacher, feminine)

This productivity allows Polish speakers to coin new words for modern phenomena while maintaining morphological consistency.

Dialectology

Major Dialect Groups

Polish dialects are traditionally grouped into four major regional varieties, each with distinct phonological, lexical, and grammatical features:

| Dialect | Region | Key Features |

|---|---|---|

| Greater Polish | West/Northwest | Historical basis for standard language; relatively conservative phonology |

| Lesser Polish | South/Southeast (Kraków region) | Distinctive vowel pronunciations; significant cultural prestige |

| Masovian | Central/East (Warsaw region) | Forms the basis of modern Standard Polish; most widely recognized urban dialect |

| Silesian | Southwest (Silesia) | Most distinctive; debated linguistic status; some claim separate language |

Phonological variation example: Greater Polish speakers may pronounce y differently from Masovian speakers; Lesser Polish shows vowel quality differences in words like pan (sir, Mr.).

Lexical variation: Dialects employ different terms for common items:

- “potato” — Standard: ziemniak, Some dialects: kartofel, frytuła

- “to be tired” — Standard: zmęczony, Dialect variants exist

Minority Languages: Silesian and Kashubian

Silesian: The status of Silesian has been subject to considerable scholarly and political debate. Some linguists argue for its classification as a separate language distinct from Polish, while others classify it as a dialect with significant deviations. In 2024, the Polish parliament passed legislation recognizing Silesian as a regional language, reflecting cultural and political developments. However, the president subsequently vetoed the law, reigniting the debate. Silesian maintains its own ISO 639-3 code (szl), indicating international recognition of its distinctness.

Kashubian: Spoken primarily along the Baltic coast (Pomerania region), Kashubian is linguistically more distinct from Standard Polish than Silesian. Notable features include:

- A nine-vowel system (compared to Polish’s six oral vowels), with phonemic distinctions absent in Standard Polish

- Phonemic word stress (varying placement), unlike Polish’s fixed penultimate stress

- Distinct consonant inventories and morphological patterns

- Unique lexical items reflecting maritime culture and Baltic influences

Kashubian maintains its own ISO 639-3 code (csb) and receives cultural protection through minority language policies. UNESCO recognizes Kashubian as an endangered language, though revitalization efforts continue.

Sociolinguistic Dynamics and Prescriptivism

Poland maintains a strong tradition of linguistic prescriptivism—the belief that certain language forms are “correct” and others “incorrect,” and the institutional efforts to enforce standard usage. Key institutions include:

- Polish Language Council (Rada Języka Polskiego) — issues authoritative recommendations on grammar, vocabulary, and usage

- Academic bodies — universities and linguistic institutes that publish normative guides

- Educational system — standardized curricula that teach Standard Polish as the model

Standard Polish is actively promoted through education and media, yet regional and social varieties persist, particularly in informal settings. Urban dialects (notably the Warsaw dialect) have largely been absorbed into Standard Polish through population migration and media influence, though some features survive in the speech of older generations and in specialized contexts.

Contemporary challenges: The prescriptivist tradition sometimes conflicts with linguistic change driven by young speakers, technology, and globalization. Debates continue regarding the incorporation of English loanwords, the status of new slang, and the proper form of internet-mediated communication.

Polish in the Modern World

Demographics and Global Distribution

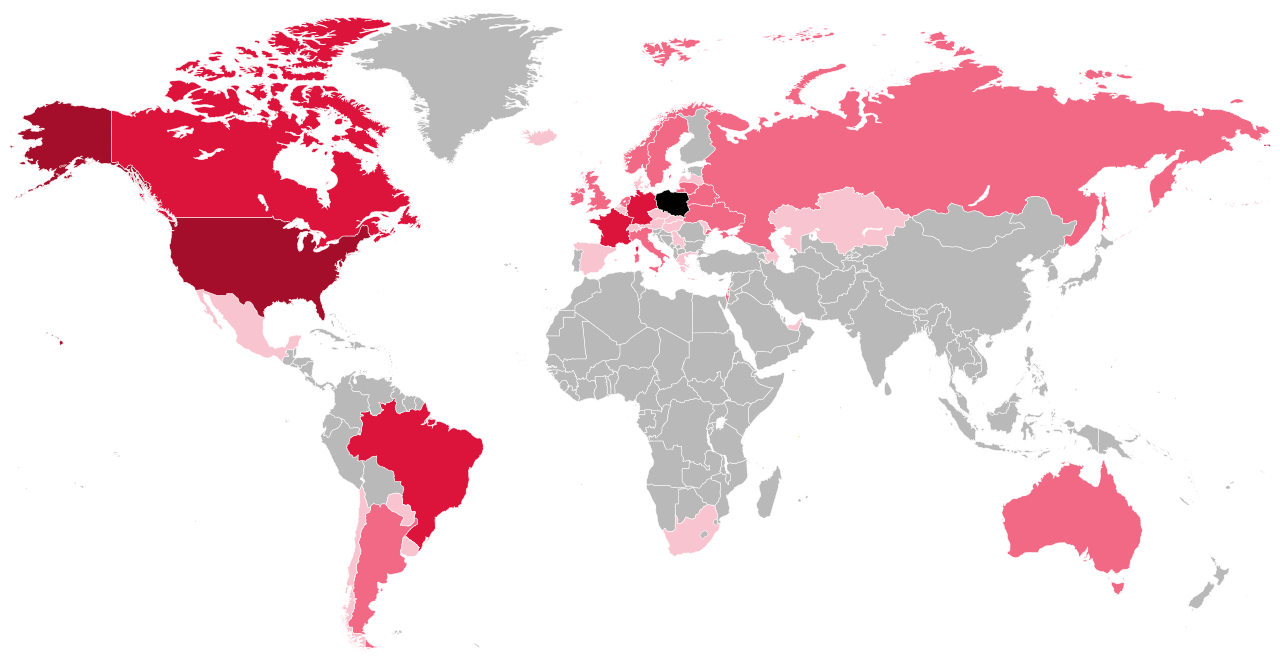

Polish boasts approximately 39.7–40 million native speakers, with total speakers (including second-language users) estimated at 60 million or more. This significant speaker base ranks Polish among Europe’s major languages.

Geographic distribution:

- Primary territory: Poland (38 million speakers)

- Neighboring countries: Significant communities in Lithuania, Belarus, Ukraine, and the Czech Republic, totaling roughly 2-3 million speakers

- Diaspora communities:

- North America: United States (~3 million), Canada (~~350,000)

- South America: Brazil, Argentina

- Western Europe: UK, Germany, France

- Oceania: Australia

Polish diaspora communities maintain varying degrees of language maintenance, influenced by immigration patterns, generational factors, and local language policies. Newer emigration waves (post-EU accession in 2004) have created vibrant Polish-speaking communities in Western Europe, particularly the UK, Germany, and Ireland.

Official Status and Language Policy

Domestic status: Polish is the sole official language of Poland, enshrined in the Polish Constitution. The language is the medium of education, government, law, and public administration.

International status: Polish serves as one of 24 official languages of the European Union, with full linguistic parity in EU institutions. This status reflects Poland’s EU membership since 2004 and ensures that all EU documents are translated into Polish.

Minority-language recognition: Polish holds minority-language status in:

- Czech Republic (Prague and surrounding regions)

- Slovakia (border areas)

- Hungary (small communities)

- Lithuania (historically significant communities)

- Ukraine (eastern regions)

Language policy instruments:

- Constitutional protections for Polish speakers’ rights

- State support for Polish language education abroad

- Cultural institutes (e.g., the Polish Institute/Institut Polski) that promote Polish language and culture globally

- UNESCO recognition of Polish as part of Europe’s linguistic heritage

Polish as a Gateway to Slavic Studies

For students and scholars, Polish occupies a strategically valuable position within Slavic linguistics. Its intermediate position between East and South Slavic language characteristics makes it an excellent analytical bridge:

- Shared features with East Slavic (Russian, Ukrainian, Belarusian): extensive case systems, perfective/imperfective verb distinction, similar phonological inventories

- Shared features with South Slavic (Bulgarian, Serbian, etc.): certain phonological features, historical sound changes

Learning Polish opens doors to understanding broader Slavic linguistic patterns and facilitates acquisition of related languages.

Literary and cultural significance: Polish literature represents one of Europe’s richest traditions, spanning centuries:

- Renaissance: Jan Kochanowski (1530–1584), regarded as the greatest Polish poet, established Polish as a language of high literature and philosophical expression

- Romanticism: Adam Mickiewicz, Juliusz Słowacki, representing Polish national identity during periods of foreign partition

- 20th century: Multiple Nobel laureates in Literature:

- Wisława Szymborska (1996) — philosophical poetry; master of irony and intellectual precision

- Czesław Miłosz (1980) — poet, essayist, and philosopher; chronicled 20th-century European history

- Henryk Sienkiewicz (1905) — historical novelist whose works remain beloved worldwide

Access to these literary traditions through Polish-language reading provides unmediated encounters with some of Europe’s finest intellectual and artistic achievements.

Conclusion

Polish is a complex and rewarding language that encapsulates the history, culture, and linguistic sophistication of Central Europe. Its intricate morphological system—with seven cases, aspectual verb distinctions, and rich derivational morphology—reflects centuries of linguistic evolution shaped by contact with German, Latin, French, and other languages, while maintaining a strong Slavic core.

The language’s sophisticated phonology, featuring palatalized consonants and a distinctive stress system, contributes to its characteristic sound. Its flexible syntax, enabled by case marking, permits elegant and expressive word ordering that serves information structure and stylistic purposes.

Contemporary Polish faces both traditional challenges (dialect leveling, linguistic prescriptivism) and modern ones (rapid technological change, loanword integration, code-switching in multilingual contexts). Yet the language remains vibrant, adaptive, and dynamic—spoken by millions, studied worldwide, and enriched by ongoing literary and intellectual contributions.

For learners, Polish offers not merely grammatical complexity but a gateway to Slavic linguistics, Central European history, and a profound literary heritage spanning from medieval manuscripts to contemporary Nobel Prize winners. For linguists, Polish provides fertile ground for exploring questions of language contact, standardization, dialect dynamics, and the relationship between linguistic structure and cultural identity.

A thorough understanding of Polish—its phonology, morphology, syntax, and sociolinguistics—enhances linguistic competence broadly and opens doors to the cultural richness of Poland and its global diaspora. Through Polish, the wider world of Slavic languages, Central European history, and European cultural diversity becomes more fully accessible and intelligible.

References for Further Study

- Comrie, Bernard, & Corbett, Greville G. (eds.). The Slavonic Languages. Oxford University Press.

- Klemensiewicz, Zbigniew. Historia języka polskiego. Państwowe Wydawnictwo Naukowe.

- Łoś, Jan, & Kuraszkiewicz, Władimir. Foneyka i morfologia języka polskiego.

- Swan, Oscar E. First Year Polish. Columbia University Press.

- Wróbel, Henryk. Gramatyka języka polskiego. Wydawnictwo RM.

- Online Polish Translator: https://openl.io/translate/polish

- Polish Language Council official resources: https://www.rjp.pan.pl/