Shakespearean English: A Practical Guide to the Language of the Bard

TABLE OF CONTENTS

1. What Is “Shakespearean English”?

“Shakespearean English” is not a separate language, but a literary form of Early Modern English (roughly 1500–1700). It’s the English of Shakespeare’s stage—close enough to modern English to recognize, yet different enough to feel archaic in spelling, vocabulary, and style.

Shakespeare wrote at a moment when English was rapidly expanding. New words entered from Latin, Greek, French, and Italian. Grammar was stabilizing but still flexible. Printing was spreading standard spellings, though variation remained common. The result is a language that can sound both familiar and startlingly inventive, providing the first written record for over 1,700 words in the English language.

2. Historical and Cultural Context

Shakespearean English reflects the educated London dialect of the late 16th and early 17th centuries. It wasn’t how every English speaker talked, but it was a prestige urban variety shaped by the Renaissance, the Reformation, the growth of theatre, and early printing. It sits between Middle English (Chaucer) and Present-Day English, serving as a crucial bridge.

Social Registers in the Plays

Shakespeare’s characters speak differently based on social class and emotional state:

| Character Type | Language Features | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Nobility | Verse (Iambic Pentameter), formal rhetoric | Hamlet, Portia |

| Citizens / Merchants | Mix of verse and prose | Shylock, Antonio |

| Commoners | Prose, colloquial speech | Bottom, Dogberry |

| Fools / Clowns | Wordplay, riddles, subversive wit | Feste, Touchstone |

This stratification reflects Elizabethan society while serving dramatic purposes. Crucially, characters often shift registers: a noble might switch to prose when they lose their sanity (like Ophelia) or are joking with friends.

3. How It Sounds: Pronunciation Notes

We cannot know Shakespeare’s pronunciation with certainty, but historical linguistics gives a clear picture. Key features of Original Pronunciation (OP) include:

- Rhotic /r/: “r” was pronounced after vowels (similar to general American or Irish accents), so “word” sounded like /wɔrd/.

- The Great Vowel Shift in progress: Long vowels hadn’t reached modern values yet.

- Different vowel qualities: “love” /lʊv/ rhymed with “prove” /prʊv/; “reason” sounded like “raisin.”

- Pronounced suffixes: “walked” could be two syllables /ˈwɔːkɛd/ when required by the meter.

Why This Matters

Understanding OP explains puzzling features:

Broken rhymes now work: “love/prove,” “groan/gone,” “war/far.”

Hidden puns emerge: “hour” and “whore” were homophones /huːr/; “nothing” and “noting” were nearly identical (crucial for Much Ado About Nothing).

Modern productions increasingly use OP to recover these lost meanings and the earthier texture of the language.

4. Grammar at a Glance

Shakespeare’s grammar is mostly modern, with recurring differences that can trip up new readers.

4.1 Pronouns: thou vs. you

Shakespeare uses a two-level system with dramatic implications:

| Form | Function | Example |

|---|---|---|

| thou / thee / thy / thine | singular informal, intimate, or implying inferiority/insult | ”Where art thou?“ |

| you / ye / your / yours | plural or formal singular | ”I thank you.” |

Dramatic shifts matter: In King Lear, Lear uses “you” to Cordelia when angry, but returns to “thou” when reconciled. In Twelfth Night, Sir Toby Belch advises Sir Andrew to “taunt him with the license of ink: if thou thou’st him some thrice, it shall not be amiss” (Act 3, Scene 2)—meaning calling a gentleman “thou” was a deliberate insult.

4.2 Verb endings

- -est with thou: thou speakest, thou art, thou hast

- -eth / -th with third-person: he speaketh, she doth, it seemeth

- -s forms (increasingly common): he speaks, she does

Shakespeare uses both -eth and -s endings, often choosing one over the other to fit the rhythm of the line.

4.3 Word order and “do”

Questions and emphasis allow greater flexibility:

- “What say you?” (modern: “What do you say?”)

- “Think you I am no stronger than my sex?”

- “Goes he hence tonight?”

The auxiliary do appears, but not always where modern English requires it (and sometimes where modern English forbids it).

4.4 Common contractions

- ‘tis = it is

- ‘twas = it was

- ne’er = never

- o’er = over

- ta’en = taken

5. Vocabulary: Familiar Words, Different Meanings

Many Shakespearean words look modern but mean something else—these “false friends” cause the most confusion:

| Word | Then | Now | Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| conceit | idea, imagination | vanity | ”in my mind’s conceit” |

| presently | immediately | at the moment | ”I’ll come presently” |

| jealous | suspicious, anxious | possessive envy | ”be not jealous on me” |

| sad | serious, solemn | unhappy | ”with a sad brow” |

| soft! | wait, hold on | gentle | ”But soft! What light…“ |

| doubt | suspect, fear | lack certainty | ”I doubt some foul play” |

| still | always, constantly | motionless / yet | ”she still loves him” |

| fond | foolish, doting | affectionate | ”fond fool” |

| nice | precise, trivial | pleasant | ”a nice distinction” |

| naughty | wicked, worthless | misbehaving | ”naughty world” |

Shakespeare is also credited with popularizing or recording hundreds of words and phrases for the first time, including assassination, swagger, break the ice, and wild-goose chase.

6. Style and Poetic Techniques

6.1 Iambic pentameter

Much dialogue follows five pairs of unstressed-stressed beats (da-DUM da-DUM da-DUM da-DUM da-DUM):

“But, SOFT! what LIGHT through YONDER WINDOW BREAKS?”

When the meter breaks, it signals emotional intensity, interruption, or status shifts. Lower-class characters often speak prose (no fixed rhythm) instead of verse.

6.2 Rhetoric and wordplay

Expect dense figurative language:

- Metaphor: “All the world’s a stage”

- Antithesis: “To be, or not to be” / “Fair is foul, and foul is fair”

- Puns: Mercutio’s “grave man” (serious / in a grave)

- Alliteration: “Full fathom five thy father lies”

- Anaphora: “This blessed plot, this earth, this realm, this England”

Reading aloud helps you catch these sound effects.

7. How to Read Shakespearean English Without Getting Lost

Before You Start

- Use a modern-spelling edition with notes (Folger, Arden, or Pelican editions).

- Read the scene summary first—knowing the plot makes language processing easier.

- Watch a performance if possible—actors clarify meaning through delivery.

While Reading

Look for the main verb: Word order often delays or inverts it.

“To the king’s ship, invisible as thou art, there shalt thou find the mariners”

Main verb: “shalt find”

—The Tempest, Act 1, Scene 2

Track pronouns carefully: thou/you shifts signal relationship changes.

Read syntactic units, not lines: Sentences run across line breaks. Pause only at punctuation marks.

Watch for inversions: “Know you not” = “Don’t you know.”

Dealing with Difficult Passages

Step 1: Paraphrase in plain modern English.

Original: “The quality of mercy is not strained; It droppeth as the gentle rain from heaven” (The Merchant of Venice, Act 4, Scene 1)

Paraphrase: “Mercy cannot be forced; it falls naturally like soft rain.”

Step 2: Return to see how meaning is built through metaphor, rhythm, and word choice.

Step 3: Read aloud—Shakespeare wrote for sound, not silent reading.

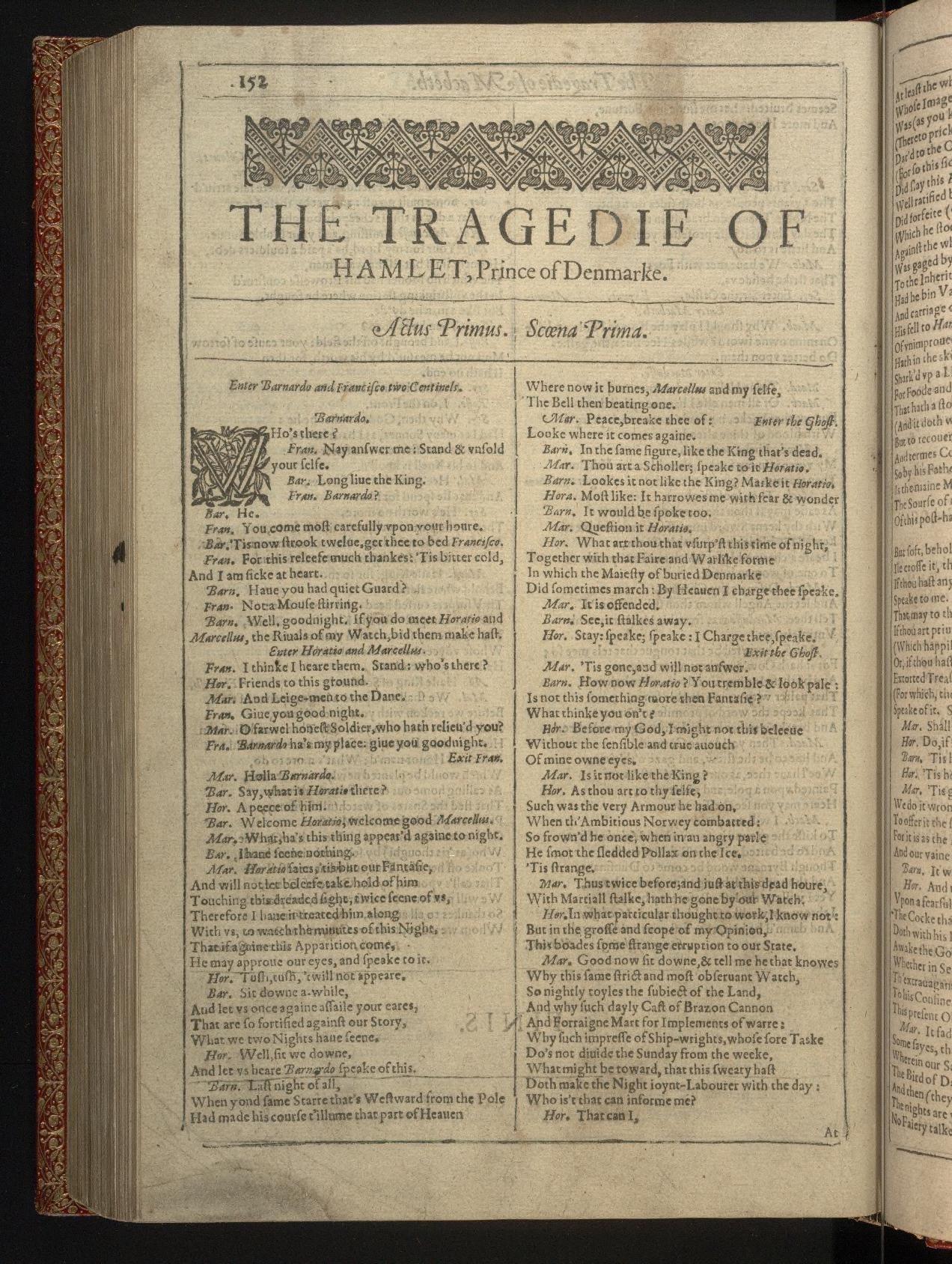

8. Case Study: Hamlet’s Soliloquy

Let’s apply these techniques to a famous passage:

“To be, or not to be—that is the question:

Whether ‘tis nobler in the mind to suffer

The slings and arrows of outrageous fortune,

Or to take arms against a sea of troubles

And, by opposing, end them.”

Analysis:

- Perfect antithesis opening: “be / not be.”

- ‘tis = it is (contraction for meter).

- “outrageous” = excessive, violent (stronger than the modern meaning).

- Military metaphor: fortune as an archer attacking.

- Mixed metaphor: fighting the sea (suggests the futility of the struggle).

- Ambiguity: “end them” = end troubles? Or end oneself?

The passage sets up a philosophical dilemma through balanced opposites, mixing metaphors, and martial imagery contrasting with passive suffering.

9. Why Shakespearean English Still Matters

Shakespeare’s language sits at the point where English becomes recognizably modern—yet still retains older flexibility. Studying it helps you:

- understand the evolution of modern grammar and vocabulary,

- read a foundational body of world literature in its original form,

- appreciate how meaning can be shaped through rhythm, sound, and rhetoric,

- develop close reading skills for complex texts.

Even if you never plan to perform a play, learning to navigate Shakespearean English opens a door to the history of English—and to one of its most creative moments.

Need translation help? If you want quick assistance with archaic vocabulary or complex passages, modern AI tools can provide line-by-line support: https://openl.io/translate/shakespearean